Again, from clay

From the specific soil of a region, the exhibition transforms material and historical strata into artistic language. It prompts a rethinking of tradition and contemporaneity, local and global, material and immaterial. The moon jar’s curve, the shard’s edge, the fields of paint, the rhythm of video—together they render the time embedded in clay into multi-sensory experience. And as each viewer receives it, that experience itself will be reshaped, to live on in another form.

All things begin, again, from clay.

이 전시는 한 지역의 흙이 지닌 물질적·역사적 층위를 예술적 언어로 변환하고, 이를 통해 전통과 현대, 로컬과 글로벌, 물질과 비물질의 관계를 재사유하도록 한다. 관람객은 항아리의 곡선, 파편의 구조, 회화의 색면, 영상의 리듬 속에서 흙이 거쳐온 시간을 다감각적으로 경험하게 될 것이다. 그 경험은 각자의 기억과 감각 속에서 다시 변형되어, 전시 이후 또 다른 형태로 재생될 것이다.

모든 것은, 다시, 흙으로부터.

Again, from Clay

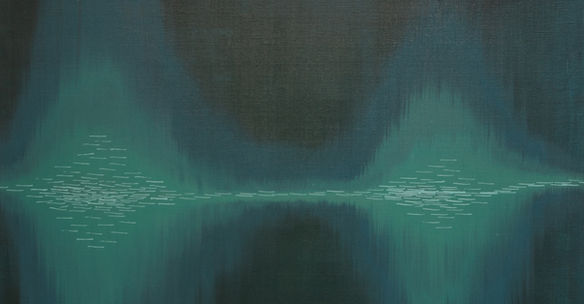

Clay is among the oldest materials handled by humankind, a medium that carries within it the traces of time and place. Its surface remembers geological strata, climate, vegetation, and the touch of human hands. The clay of a given land is never a neutral matter; it condenses history, culture, technique, and social relations. Clay is at once a record and an open language—infinitely malleable, endlessly reinterpretable.At the foot of Girin Mountain in Wangjeong-dong, Namwon-si, stands Manboksa (萬福寺), a grand Buddhist temple founded during the reign of King Munjong of Goryeo (1046–1083). Historical records note that “each morning, hundreds of monks went out to receive alms, and by evening, their return formed a magnificent scene” (Sinjeung Dongguk Yeoji Seungnam). As a spiritual and cultural hub, the temple was also surrounded by kiln sites. The clay of Wangjeong-dong, known for its fine particles and strong plasticity, withstood firing to produce durable vessels. It became the material basis for ritual implements and everyday wares, grounding the region’s ceramic tradition.This cultural resonance also appears in literature. Kim Si-seup (1435–1493), in his collection Geumo Sinhwa (New Tales of the Golden Turtle), set one of its short stories, The Tale of Playing Jeopo at Manboksa, at this very temple. The protagonist, Yang Saeng, casting dice before the Buddha, is drawn into a web of fated encounters. The narrative compresses the essence of human experience—chance and inevitability, meetings and partings—and shows how memory and relationship persist, even through war, disaster, and rupture.The exhibition Again, from Clay begins from this soil and this place. Ceramic artist Hyun-Chul Kim shaped moon jars from clay he gathered in Wangjeong-dong, then fired them over long hours, leaving their surfaces marked by fire and glaze. His process is both material experiment and a contemporary re-contextualization of tradition.Visual artist Eun-Hyung Kim extends this dialogue into painting, installation, and video. Not only intact jars but also their broken fragments become integral to the work. The shards are not treated as loss but as another form of completion, embodying the unpredictability and aesthetic of chance inherent in ceramic making. The curve of the jar reappears as waves of color in painting; fragments lean against each other to form fragile structures; memory of place returns through transparent layers of color and rhythm. Blue and green planes in painting echo the breath of the jar and the temporality of Wangjeong-dong. In installation, tree trunks and ceramic remnants together bear each other’s weight, suggesting relations across generations and materials. Video dissolves and reassembles clay, fire, form, and image in cycles, revealing their mutual transformation.The traditional idea that “all begins in clay and returns to clay” here finds new interpretation. Return is not circular repetition but altered re-arrival. As Walter Benjamin wrote of the “aura”—the unique presence conferred by time and place—even the same clay becomes entirely different depending on its trajectory of fire, fracture, and history.This exhibition attends to thresholds: between material and time, form and fragment, tradition and reinterpretation. Completion and breakage are not opposites but moments along a continuum. Shards once devoid of function form the basis for new structures. Smooth curvature and sharp fracture

presuppose each other, confronting the viewer with time’s duality. In this way, the works expand into metaphor for memory, history, and the condition of existence.

Again, from Clay visualizes a process where material becomes sensation, and sensation returns to material. Clay becomes form, form dissolves into image, image returns as perception. This is not linear narrative but cyclical shuttling, a constant reconstruction. The exhibition asks: what does it mean to “return”? Return here is not simply a recovery of the past but a new beginning at the crossing of change, persistence, disappearance, and emergence.

From the specific soil of a region, the exhibition transforms material and historical strata into artistic language. It prompts a rethinking of tradition and contemporaneity, local and global, material and immaterial. The moon jar’s curve, the shard’s edge, the fields of paint, the rhythm of video—together they render the time embedded in clay into multi-sensory experience. And as each viewer receives it, that experience itself will be reshaped, to live on in another form.

All things begin, again, from clay.

August 2025, Eun-Hyung Kim